Exploring the role of women in colonial medicine

History Associate Professor Dr. Jacqueline Holler received Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council Insight Grant to examine how women’s healing networks in New Spain in the 16th to 18th centuries contributed to the sharing of medical knowledge and materials among people of Indigenous, Spanish, and African descent, and whether in turn that knowledge found its way into learned medicine.

Our health and the health of our communities is top-of-mind for everyone during the current pandemic.

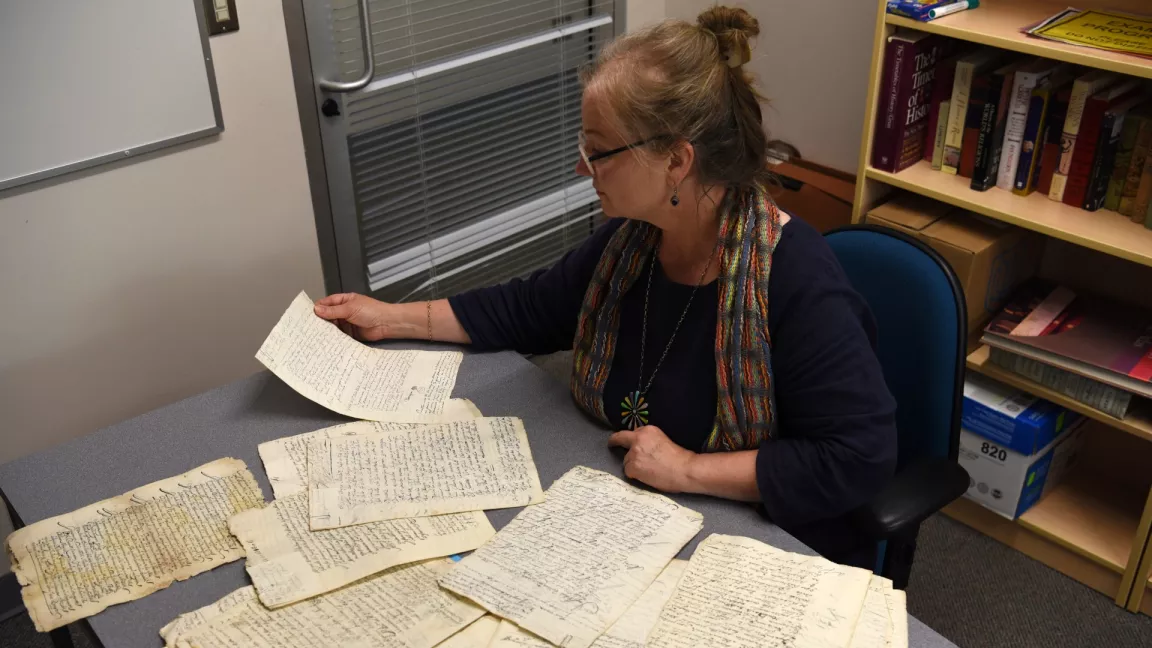

In her latest research project, University of Northern British Columbia History Associate Professor Dr. Jacqueline Holler is looking back to see how our approaches to medicine have changed over time and the role women have played in the advancement of treatment.

Holler received Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council Insight Grant to examine how women’s healing networks in New Spain in the 16th to 18th centuries contributed to the sharing of medical knowledge and materials among people of Indigenous, Spanish, and African descent, and whether in turn that knowledge found its way into learned medicine.

“Illness and health concerns are one of the most universal human experiences, as we are now seeing in our present pandemic moment,” she says. “Studying the history of health can sometimes produce knowledge that is directly relevant to our current situation.”

The project, titled Medicines, Marvels, and Mestizaje: Women’s Healing in New Spain, 1530-1750, aims to create a full picture of how early colonial people thought about health and disease and tried to cure themselves and others.

“I believe that I will learn and be able to share useful information about how people navigated health and disease in a very interesting historical context,” she says.

The grant, worth $181,948, will not only support Dr. Holler’s research but will also provide funding for two master’s students and one postdoctoral fellowship.

Holler and her team of researchers will examine medical treatises as well as convent “recipe books” that contained healing remedies, and approximately 1,400 Inquisition records that describe women’s healing activities and the herbs, medicines, and even incantations that ordinary people used to treat illness.

“There were very few physicians in colonial New Spain relative to the size of the population, so most people relied upon popular healers, nuns and friars, and their own social networks for medicines and treatments,” she says.

Holler says the location and size of UNBC has helped her gain a new perspective on her research. For instance, the vastness of northern B.C., can provide context when she is studying healers in 16th century Mexico.

“To take one example from the records I study, in 1562 a woman who developed an infected wound after injuring her foot planned to travel to Mexico City, a difficult 300-kilometre journey from her home, because she couldn’t find anyone locally who could treat the foot,” Holler explains. “I think being at UNBC has made me much more attuned to the effects of environment on the people I study.”

Conducting research at a small university also has its benefits.

“Being in a small, collegial department where I can have conversations with my colleagues who study other historical periods and regions has also enhanced my research immeasurably,” she says.